It was 196 years ago when..

It was 196 years ago when..

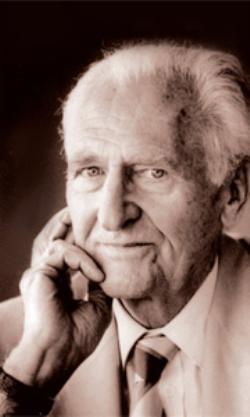

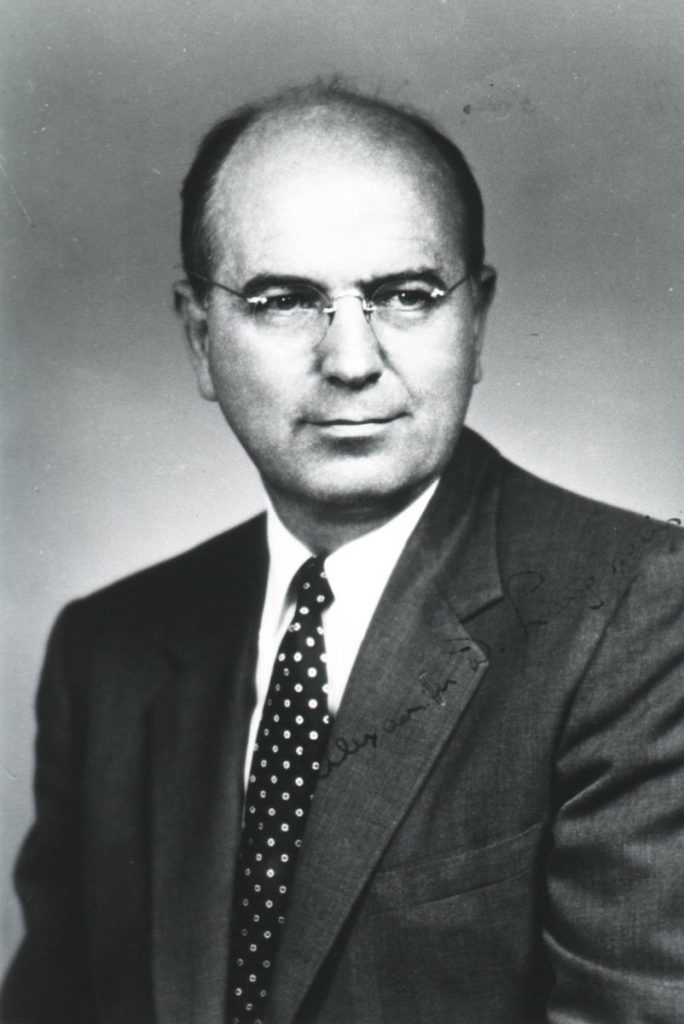

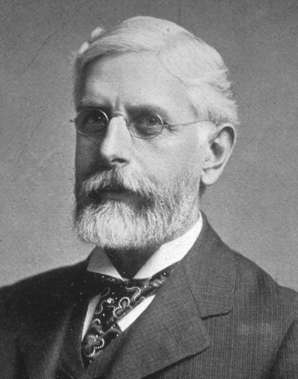

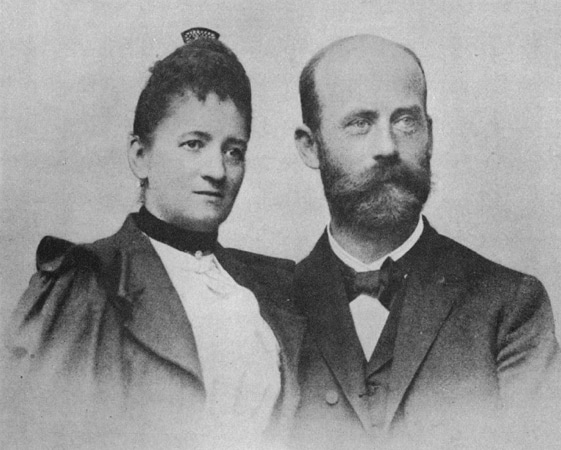

Rudolf Ludwig Carl Virchow (13 October 1821 – 5 September 1902) was born in Schievelbein in eastern Pomerania, Prussia (now Świdwin in Poland). He was the only child of Carl Christian Siegfried Virchow (1785–1865) and Johanna Maria née Hesse (1785–1857). His father was a farmer and the city treasurer. Academically brilliant, he always topped in his classes and was fluent in German, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, English, Arabic, French, Italian, and Dutch. He progressed to the gymnasium in Köslin (now Koszalin in Poland) in 1835 with the goal to become a pastor. He graduated in 1839 upon a thesis titled A Life Full of Work and Toil is not a Burden but a Benediction. However, he chose to start studying medicine mainly because he considered his voice too weak for preaching.[1] His uncle was a high-ranking officer, which may have helped him gain admission into the most prestigious medical school of the time-a military medical school in Berlin with a selective acceptance policy.[2]

The pope of medicine

It was from that medical school that Virchow would further develop into a physician, anthropologist, pathologist, prehistorian, biologist, writer, editor, and politician, known for his advancement of public health. He is known as "the father of modern pathology" because his work helped to discredit humourism, bringing more science to medicine. He is also known as the founder of social medicine and veterinary pathology, and to his colleagues, the "Pope of medicine".[1]

At the early age of 27 he was appointed to a government commission to investigate a typhus epidemic in Upper Silesia (1847-1848). At that time, typhus, typhoid, and recurrent fever were not yet clearly separated diagnostic entities. The study came at an explosive time in European and especially German history, and his report on the aetiology of the epidemic, expressed in radically antiestablishment social and political terms typified the professional radicalism of the period. [2]

"The logical answer to the question as to how conditions similar to those unfolded before our eyes in Upper Silesia can be prevented in the future is, therefore, very easy and simple: education, with its daughters, liberty and prosperity."

The ravages of the epidemic must have made a lasting impression on young Virchow, shaping not only his character, but also his professional perspective. He wrote in his report:

"A devastating epidemic and a terrible famine simultaneously ravaged a poor, ignorant and apathetic population. In a single year 10% of the population died in the Pless district, 6.48% of starvation combined with the epidemic, and, according to official figures, 1.3% solely of starvation. In 8 months, in the district of Rybnik, 14.3% of the population were affected by typhus, of whom 20.46% died. . . . At the beginning of the year, 3% of the population of both districts were orphans. . . ." [3]

Even though he was not particularly successful in combating the epidemic, his 190-paged Report on the Typhus Epidemic in Upper Silesia in 1848 became a turning point in politics and public health in Germany. From it, he coined a well known aphorism:

"Medicine is a social science, and politics is nothing else but medicine on a large scale".

He returned to Berlin on 10 March 1848, and only eight days later, a revolution broke out against the government in which he played an active part. To fight political injustice he helped finding Die medicinische Reform (Medical Reform), a weekly newspaper for promoting social medicine, in July of that year. The newspaper ran under the banners "medicine is a social science" and "the physician is the natural attorney of the poor". Political pressures forced him terminate the publication in June 1849 and became expelled from his official position. After five years, Charité invited him back to direct its newly built Institute for Pathology, and simultaneously becoming the first Chair of Pathological Anatomy and Physiology at Berlin University. The campus of Charité is now named Campus Virchow Klinikum.

Virchow was the first to precisely describe and give names of diseases such as leukemia, chordoma, ochronosis, embolism, and thrombosis. He coined scientific terms, chromatin, agenesis, parenchyma, osteoid, amyloid degeneration, and spina bifida. His description of the transmission cycle of a roundworm Trichinella spiralis established the importance of meat inspection, which was started in Berlin. He developed the first systematic method of autopsy involving surgery of all body parts and microscopic examination. A number of medical terms are named after him, including Virchow's node, Virchow–Robin spaces, Virchow–Seckel syndrome, and Virchow's triad. He was the first to use hair analysis in criminal investigation, and recognised its limitations. His laborious analyses of the hair, skin, and eye colour of school children made him criticise the Aryan race concept as a myth.

He was an ardent anti-evolutionist. He referred to Charles Darwin as an "ignoramus" and his own student Ernst Haeckel, the leading advocate of Darwinism in Germany, as a "fool". He discredited the original specimen of Neanderthal man as nothing but that of a deformed human, and not an ancestral species. He was an agnostic. [1]

Anti-germ theory of diseases

Virchow did not believe in the germ theory of diseases, as advocated by Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch. He proposed that diseases came from abnormal activities inside the cells, not from outside pathogens. He believed that epidemics were social in origin, and the way to combat epidemics was political, not medical. He regarded germ theory as hindrance to prevention and cure. He considered social factors such as poverty as major cause of diseases. He even attacked Koch's and Ignaz Semmelweis' policy of hand-washing as an antiseptic practice. He postulated that germs were only using infected organs as habitats, but they were not the cause, and stated,

"If I could live my life over again, I would devote it to proving that germs seek their natural habitat: diseased tissue, rather than being the cause of diseased tissue".Virchow said. [1]

In hindsight, he may be glad that he did not embark on such path.

Death

Virchow broke his thigh bone on 4 January 1902, jumping off a running streetcar while exiting the electric tramway. Although he anticipated full recovery, the fractured femur never healed, and restricted his physical activity. His health gradually deteriorated and he died of heart failure after eight months, on 5 September 1902, in Berlin. A state funeral was held on 9 September in the Assembly Room of the Magistracy in the Berlin Town Hall, which was decorated with laurels, palms and flowers. He was buried in the Alter St.-Matthäus-Kirchhof in Schöneberg, Berlin. His tomb was shared by his wife on 21 February 1913. [1]

"At his death Germany would complain of having lost four great men in one: her leading pathologist, her leading anthropologist, her leading sanitarian, and her leading liberal."

Erwin Ackerknecht [2]

References:

- Rudolf Virchow, in: Wikipedia, accessed 13 October 2017

- Silver GA. Virchow, the heroic model in medicine: health policy by accolade. American Journal of Public Health. 1987;77(1):82-88.

- Virchow RC. Report on the Typhus Epidemic in Upper Silesia. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(12):2102-2105.

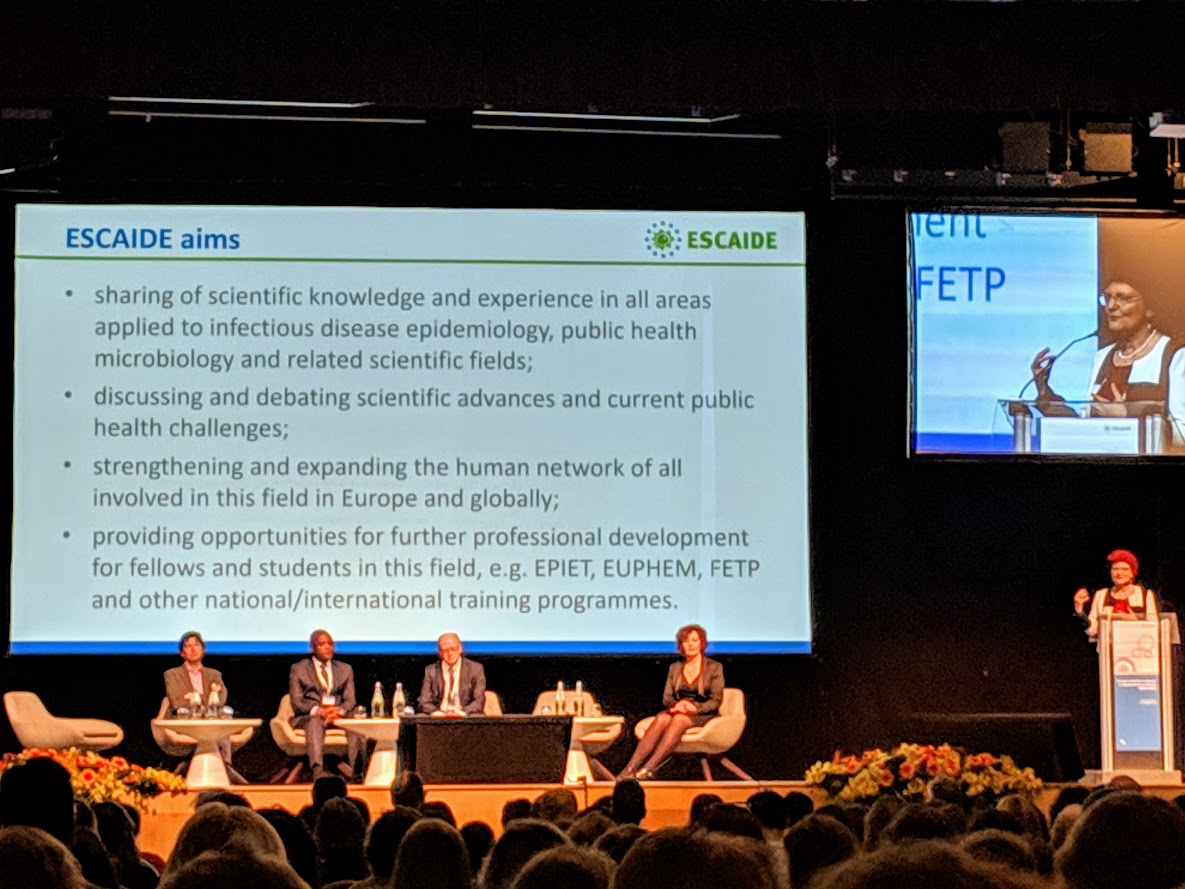

Poster Session 22 on Vaccine Effectiveness (see picture left) included 4 presentations on effectiveness of Pneumococcal Vaccines and one on seasonal influenza.

Poster Session 22 on Vaccine Effectiveness (see picture left) included 4 presentations on effectiveness of Pneumococcal Vaccines and one on seasonal influenza.

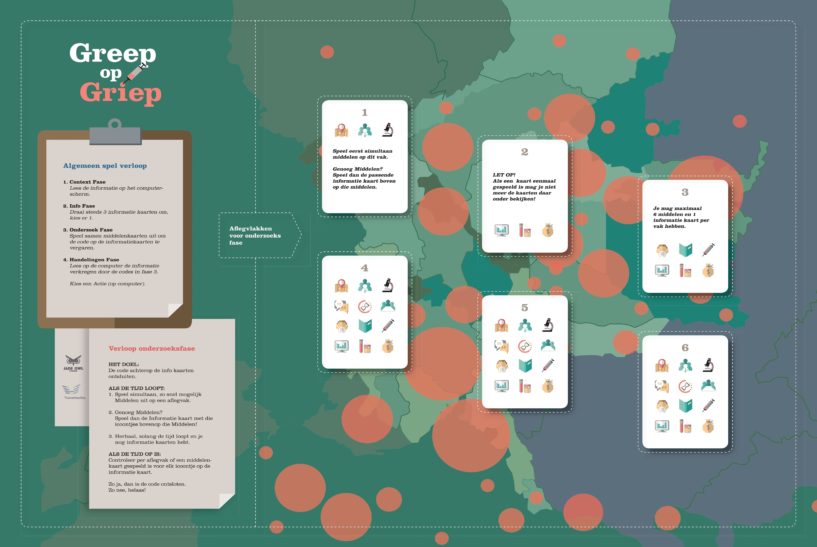

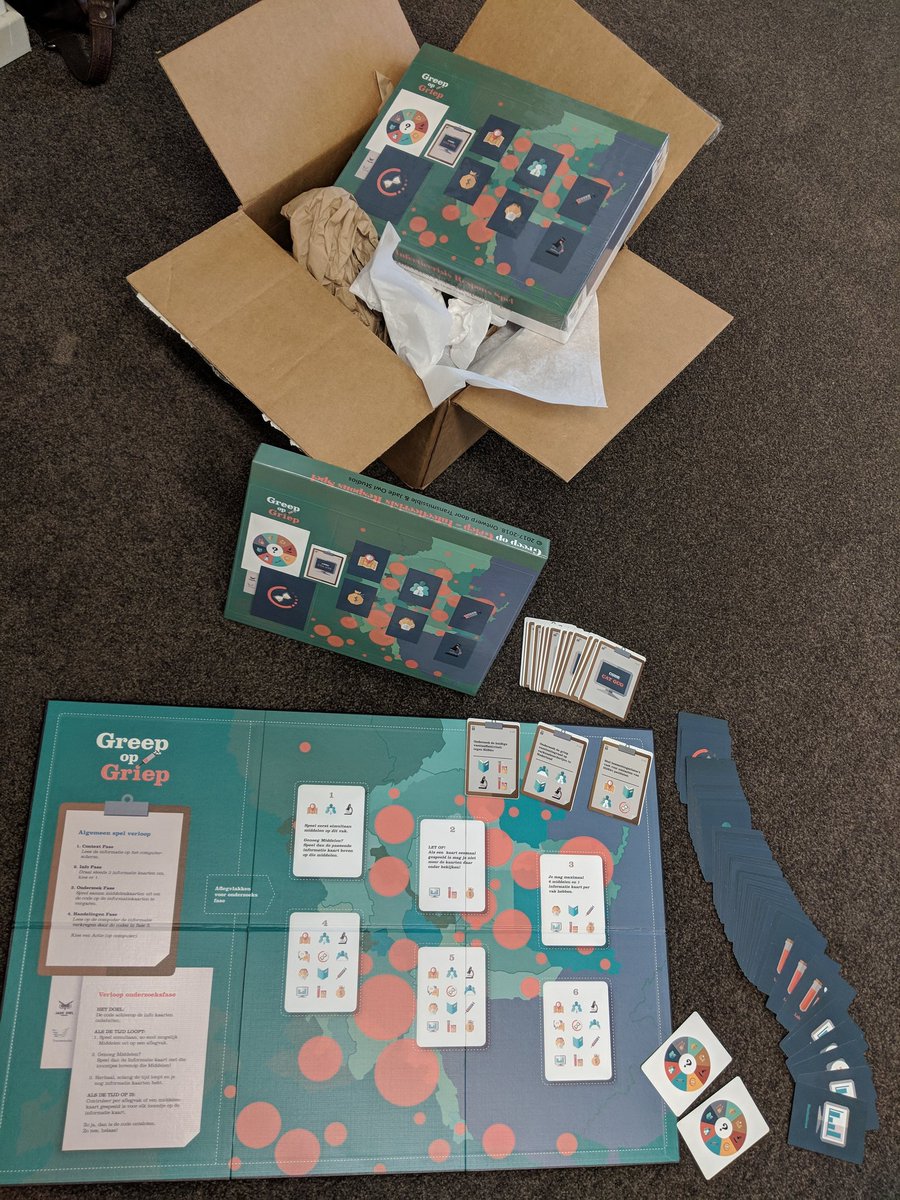

Today the new design of our game 'Greep op Griep' arrived ! So the unboxing was exciting: the new design by

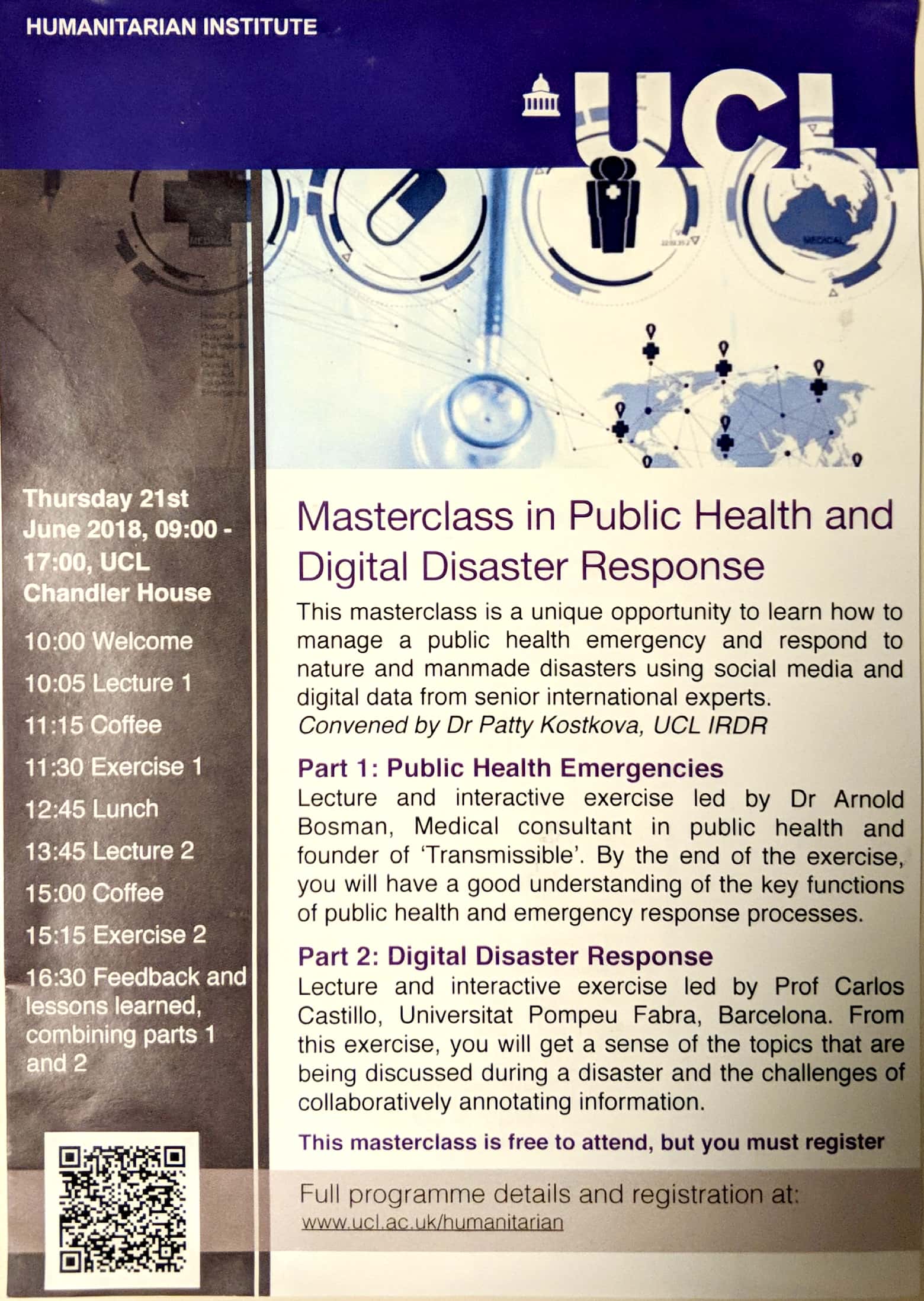

Today the new design of our game 'Greep op Griep' arrived ! So the unboxing was exciting: the new design by  On 21 June 2018, University College London (UCL) organised a Masterclass on Digital Disaster Response. Participants brought a rich and wide range of professional backgrounds, a majority of which in public health and disaster response. Dr. Patty Kostkova had convened the event, and invited Arnold Bosman from Transmissible (NL) and professor Carlos Castillo from Pompeu University (ES) to present.

On 21 June 2018, University College London (UCL) organised a Masterclass on Digital Disaster Response. Participants brought a rich and wide range of professional backgrounds, a majority of which in public health and disaster response. Dr. Patty Kostkova had convened the event, and invited Arnold Bosman from Transmissible (NL) and professor Carlos Castillo from Pompeu University (ES) to present. We have been working on this serious game in the background for the past 9 months. In November we organized the Beta-test, and last week the general rehearsal with all game-facilitators. The game has been developed by Transmissible and Jade Owl Studios, in an assignment from the Julius Centre at the University Medical Centre of Utrecht (NL).

We have been working on this serious game in the background for the past 9 months. In November we organized the Beta-test, and last week the general rehearsal with all game-facilitators. The game has been developed by Transmissible and Jade Owl Studios, in an assignment from the Julius Centre at the University Medical Centre of Utrecht (NL).

For the past six years, Syria’s children have been bombed, shot at and starved to death. They’ve seen loved ones killed or injured, right before their eyes. Their homes and schools reduced to rubble. Their families torn apart.

For the past six years, Syria’s children have been bombed, shot at and starved to death. They’ve seen loved ones killed or injured, right before their eyes. Their homes and schools reduced to rubble. Their families torn apart. Influenza Escalates

Influenza Escalates Karel Raška (17 November 1909 – 21 November 1987) born in the South Bohemian town Strašín, in what is now Czech Republic. He was a physician and epidemiologist, who headed the successful international effort during the 1960s to eradicate smallpox. Raska was a Director of the WHO Division of Communicable Disease Control since 1963. His new concept of eliminating the disease was adopted by the WHO in 1967 and eventually led to the eradication of smallpox in 1977.[1] Raška was also a strong promoter of the concept of disease surveillance, which was adopted by WHO in 1968 and has since become a standard practice in epidemiology.[2]

Karel Raška (17 November 1909 – 21 November 1987) born in the South Bohemian town Strašín, in what is now Czech Republic. He was a physician and epidemiologist, who headed the successful international effort during the 1960s to eradicate smallpox. Raska was a Director of the WHO Division of Communicable Disease Control since 1963. His new concept of eliminating the disease was adopted by the WHO in 1967 and eventually led to the eradication of smallpox in 1977.[1] Raška was also a strong promoter of the concept of disease surveillance, which was adopted by WHO in 1968 and has since become a standard practice in epidemiology.[2]

It was 196 years ago when..

It was 196 years ago when.. ..when Alexander Duncan Langmuir was born in Santa Monica, California. He spent his youth in New Jersey. His uncle, Irving Langmuir won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1932. At Harvard College, Alex Langmuir received his AB (cum laude) in 1931 and his MD in 1935 from Cornell University Medical College.[3]

..when Alexander Duncan Langmuir was born in Santa Monica, California. He spent his youth in New Jersey. His uncle, Irving Langmuir won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1932. At Harvard College, Alex Langmuir received his AB (cum laude) in 1931 and his MD in 1935 from Cornell University Medical College.[3] Thomas Sydenham was born on 10 September 1624 at Wynford Eagle in Dorset. He was an English physician and the author of Observationes Medicae which became a standard textbook of medicine for two centuries. This earned him the predicate 'The English Hippocrates'. Among his many achievements was the discovery of a disease, Sydenham's Chorea, also known as St Vitus Dance. [1]

Thomas Sydenham was born on 10 September 1624 at Wynford Eagle in Dorset. He was an English physician and the author of Observationes Medicae which became a standard textbook of medicine for two centuries. This earned him the predicate 'The English Hippocrates'. Among his many achievements was the discovery of a disease, Sydenham's Chorea, also known as St Vitus Dance. [1]

It was 129 years ago today......

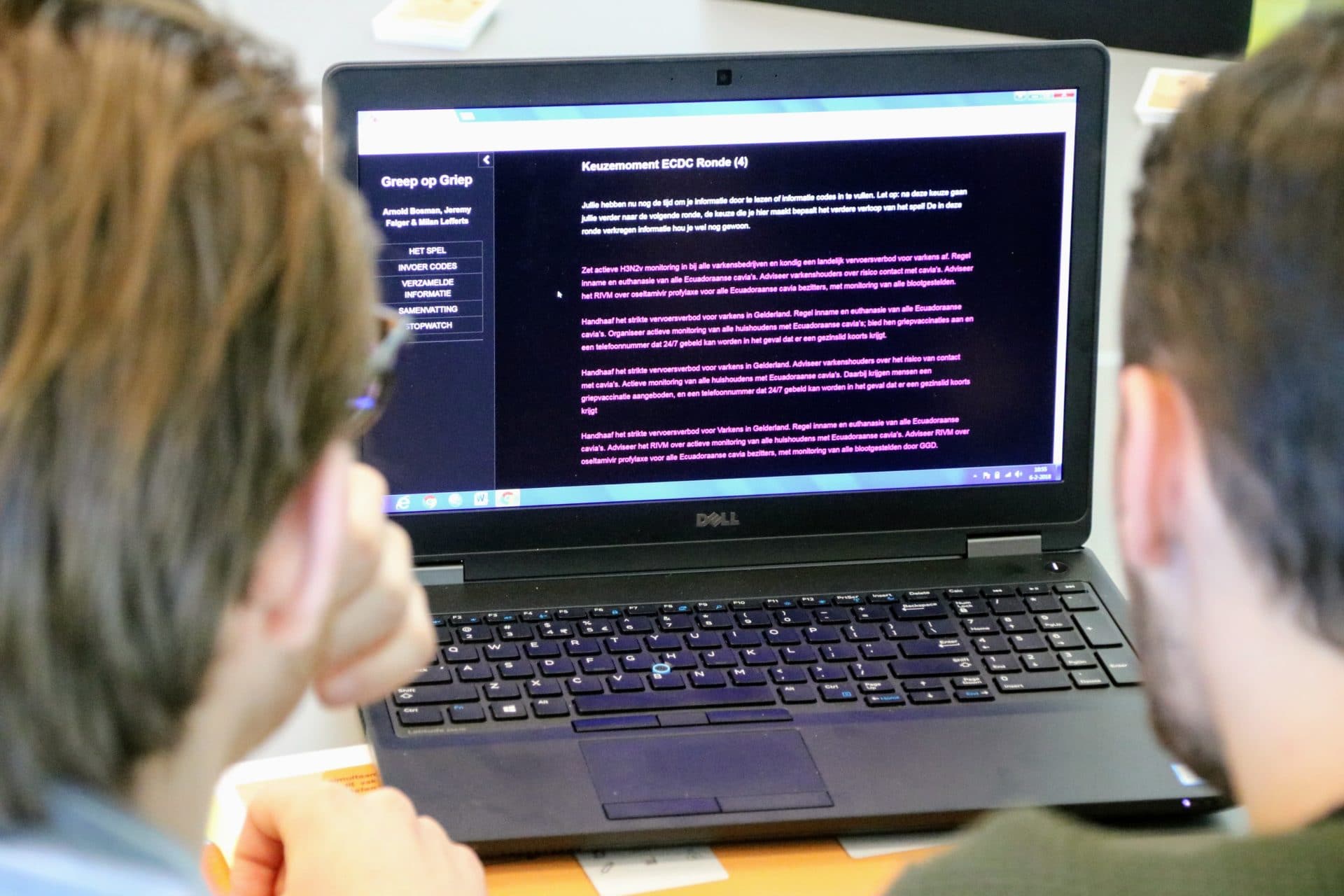

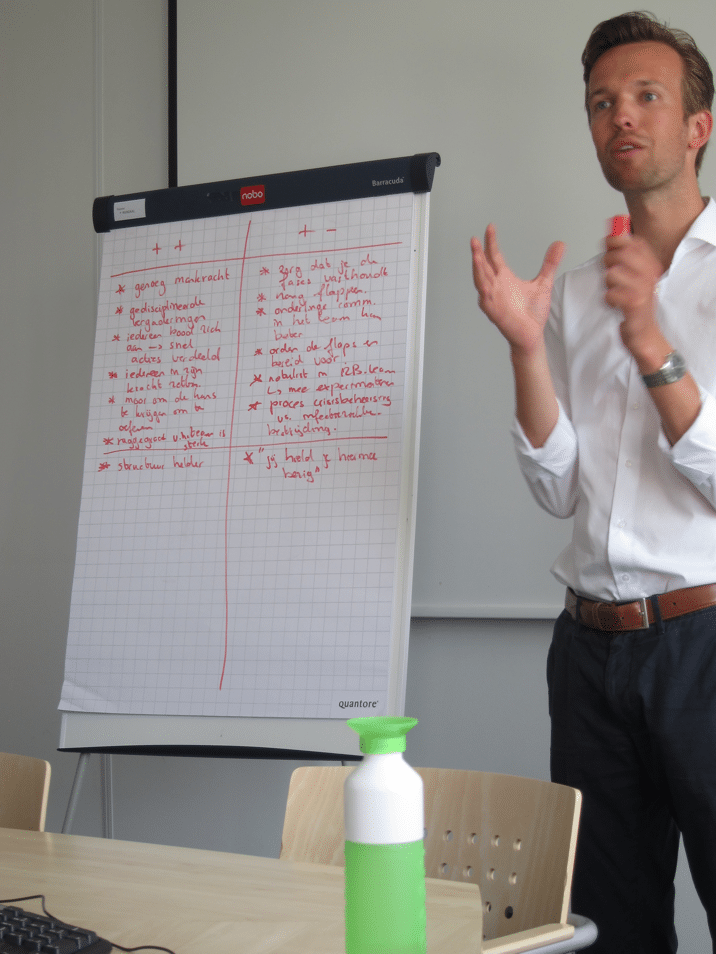

It was 129 years ago today...... A large group of people gets contaminated with a virulent pathogen, and regular treatment is ineffective. To make matters worse, the control measures are interrupted by increasing civil unrest. The Communicable Disease Control team of the Public Health Service 'Hollands-Midden', dared to engage in this scenario during a training workshop.

A large group of people gets contaminated with a virulent pathogen, and regular treatment is ineffective. To make matters worse, the control measures are interrupted by increasing civil unrest. The Communicable Disease Control team of the Public Health Service 'Hollands-Midden', dared to engage in this scenario during a training workshop.

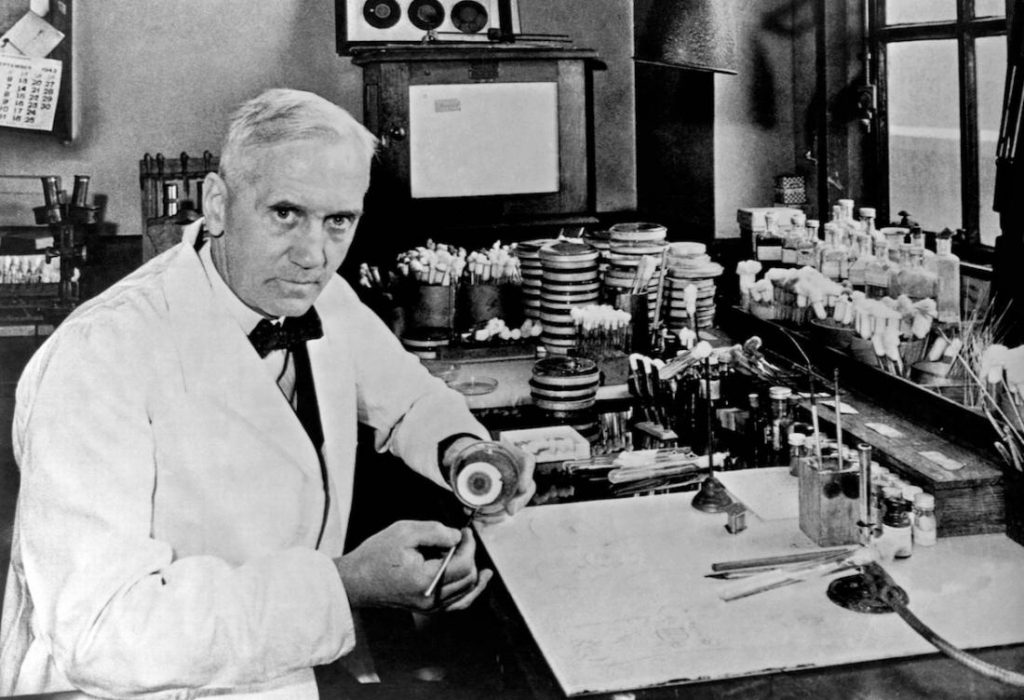

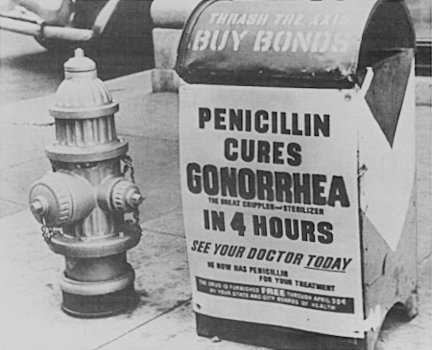

In the 1930s, Fleming’s trials occasionally showed more promise, and he continued, until 1940, to try to interest a chemist skilled enough to further refine usable penicillin. Fleming finally abandoned penicillin, and not long after he did, Howard Florey and Ernst Boris Chain at the Radcliffe Infirmary in Oxford took up researching and mass-producing it, with funds from the U.S. and British governments. They started mass production after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. By D-Day in 1944, enough penicillin had been produced to treat all the wounded in the Allied forces.

In the 1930s, Fleming’s trials occasionally showed more promise, and he continued, until 1940, to try to interest a chemist skilled enough to further refine usable penicillin. Fleming finally abandoned penicillin, and not long after he did, Howard Florey and Ernst Boris Chain at the Radcliffe Infirmary in Oxford took up researching and mass-producing it, with funds from the U.S. and British governments. They started mass production after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. By D-Day in 1944, enough penicillin had been produced to treat all the wounded in the Allied forces. It was 167 years ago today....

It was 167 years ago today.... It was 120 years ago, today

It was 120 years ago, today

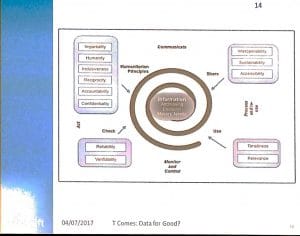

Developing new systems for humanitarian aid is a complex matter, and the worst thing one could do, is rolling out a new system during a crisis. Gomes illustrated this with an example from the 2014-2015 Ebola response.

Developing new systems for humanitarian aid is a complex matter, and the worst thing one could do, is rolling out a new system during a crisis. Gomes illustrated this with an example from the 2014-2015 Ebola response.

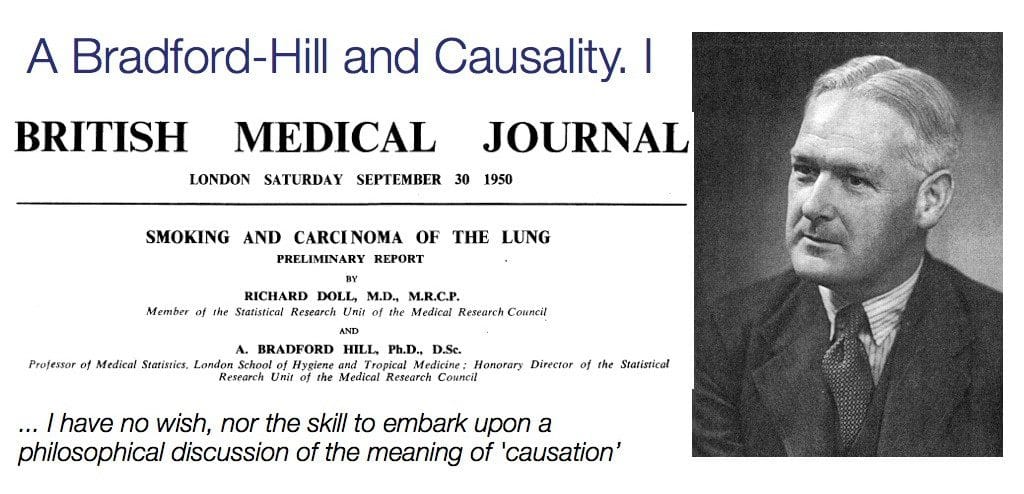

It was 106 years ago today when William Haenszel was born in Rochester, New York.

It was 106 years ago today when William Haenszel was born in Rochester, New York. It is already a year ago that Transmissible was established in the Netherlands. And since June 1, 2016, the little boy has learned to walk.

It is already a year ago that Transmissible was established in the Netherlands. And since June 1, 2016, the little boy has learned to walk.